Many at UTSA know Sidury Christiansen, an associate professor in the UTSA College of Education and Human Development, for her impressive research, which focuses on the connection between language and culture. However, what might surprise them is the fact that several times each year you can see her swaying the hem of a ballet folklórico dress as she twirls on stage with members from the “Grupo Folklórico Los Correcaminos de UTSA”, also known as Ballet Folklórico de UTSA, a group she founded in 2017.

La danza folklórica became a part of Christiansen’s life more than 40 years ago, when she was living in the small village of Altotonga, Mexico. Today, she is sharing this talent and passion with students at UTSA to create an outlet at the university for our students to keep the culture alive. It is more than steps and music. It’s about telling stories, preserving traditions, and building sense of community.

Sombrilla Magazine sat down with Christiansen to learn why she continues to dance today and how ballet folklórico is connecting students to their culture.

How did you get started with danza folklórica?

SC: I first started to dance as a child. I’m from a very, very small town in Mexico. The opportunities were very limited. This dance instructor happened to be looking to show the students in the village how to dance. I remember my teacher saying, “Oh, my goodness, we have this opportunity. This guy is going to come nearby to teach children the folklórico dance.” It was the talk of the town. I’m not from a well-off family. We struggled to make ends meet. My mother told my teacher “mis hijos” couldn’t participate, and as children, we knew it was because of money.

But that didn’t get to me. I signed up anyway. I started going to the practices, and they noticed that it was easy for me to pick up. I would just see the teacher and immediately copy the step and memorize the entire choreography.

He would put me in the front of the class as an example. When the performance came, they called my mom and said, “Your daughter needs the attire,” but my mom did not know what I had been doing.

The people in our village came together to get me to the dance, and some other mother did the braids, and another was the seamstress. Since then, I think my mom understood what it meant to me.

The dance that we learned at that time was from the state of Chiapas, which is a very a popular dance. It’s like the one where you clap. It’s not difficult in the footwork. That was the first dance I taught the students after we revived the group at UTSA from COVID.

This is how culture gets passed on. I mean, I learned this almost 40 years ago from these older people, and now I’m passing this on. I just think that’s cultural wealth that gets passed on.

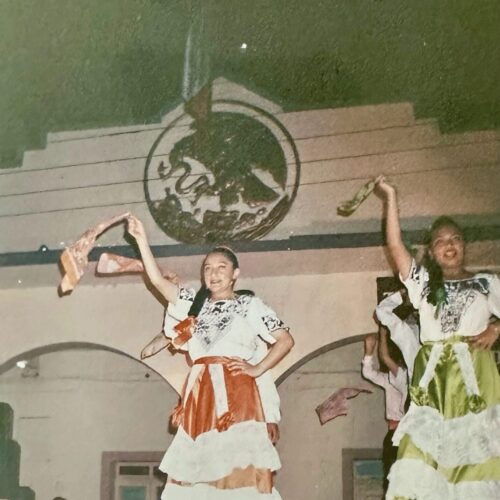

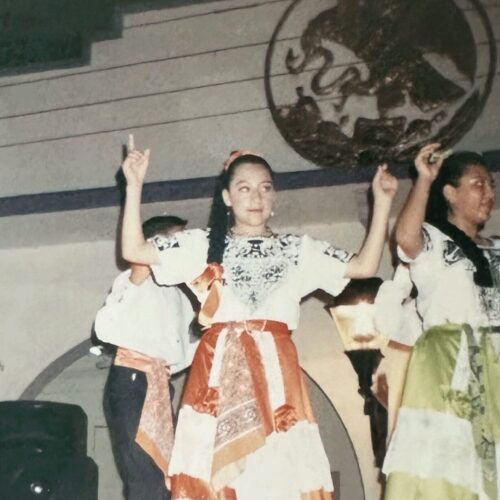

Christiansen performs at the Market Square in San Antonio.

Photos from throughout the years of Christiansen performing in Mexico.

This is a wonderful story of your perseverance as a child. Did you continue dancing while you were older in school?

SC: On and off I did. Not all schools have money to have these programs. People were privileged if they had the money to pay for the costumes and everything. When I did it in elementary, I could only do the one dance because that’s the only costume I had. I didn’t have all the other outfits required for the other dances, but I knew all of them because I did them in practice.

I didn’t dance for two years until we moved to the capital city of Xalapa, Veracruz, and I went to a different middle school that had a folklórico dancing group with their own costumes that would lend them to us. While at this new school, our teacher was friends with one of the most prominent jaracho music groups, Tlen Huicani.

This renowned international group would come play for us as we danced. Getting to dance to the live sounds of the arpa and jarana and not just a tape made me more passionate about dancing. And so, I learned to dance more rhythms, and the repertoire got better. I got more interested about the different cultures of Mexico and where the dances come from. I learned about the significance of the attire and the placement of the flowers, and most importantly the histories of people who made them.

You’re sharing this cultural wealth with UTSA students, but have you had the opportunity to share it outside the university?

SC: During my undergrad, I came to study abroad in Indiana and was a cultural ambassador as part of my scholarship. As an ambassador, they were looking for people to showcase their culture. So, I’m like, “Hey, I can dance!” I was always involved in cultural affair activities while in Indiana.

And so, I did a few performances, and it still came natural to me.

When I moved to the US to attend Indiana University—Purdue University Fort Wayne for my master’s, I started working in the community, and I recognized a need. A lot of people want to hold on to the culture. When immigrant mothers in the community would find out I could dance, they told me, “Let’s get together to teach the children.”

I used to teach at community centers in Indiana, and then in Ohio, while I studied my Ph.D., I saw the need in the community. And when I came here, I saw that same need at UTSA.

A member from Ballet Folklórico de UTSA dances at the Light the Paseo event on Main Campus.

How did the idea to start the dance group at UTSA come about?

SC: I’ve always wanted to do one, but, as an assistant professor, my job is to do research and other things. I teach sociolinguistics, and I talk about culture and language together. When I talk about culture, I always share how I can dance. Dance is also language. At some point, one of my students said, “Oh, you dance folklórico, really? If you know how to dance, then why aren’t you teaching dance?”

I hesitated. I’m not an ethnomusicologist or a professionally trained dance teacher or a dance educator, but I respect a lot of people that do this work. I mean, they get degrees in this, and here I am an amateur dancer. I just have a passion for the dance and for great music.

But this student pushed me to get the group going in 2017, and she had some friends who were already experienced and very interested to continue performing after their high school years. The group went on to win some competitions, but after COVID hit, the group kind of slowed down, primarily because of lack of support. Even though we are an official student organization with the school, we do not belong to an official program at UTSA. So finding room to practice with adequate flooring and fundraising for more costumes and not being a structured part of an official program makes it difficult for students to add it to their official class schedule. But we now have new students, and they are doing a wonderful job reviving it. They now have more than now 20 members. They are thriving.

WATCH NOW: Ballet Folklórico de UTSA close out the Jovita Idar Quarter Release event.

What impact do you feel that the ballet folklórico group has on students?

SC: It gives students a sense of belonging. Anyone can participate.

I’ve found in my research when you help students find that sense of belonging, they stick around. They do better, which is what I noticed with those who have participated in the dance group.

There was a student who was in the group, and she invited us to perform at her company’s annual meeting. She had already graduated, and she told me that being in the group made her feel very proud and defined her time at UTSA.

Even if someone isn’t performing and they are there to watch us, they have a feeling that “Oh, this is my culture!”

We are keeping the culture and traditions alive. If you think about it, a dance I learned 40 years ago in rural Mexico is being passed on, and in some years from now, it will be passed onto another new group of dancers in another 40 years

No comment yet, add your voice below!