Cody Cly was raised on a Navajo reservation in the small community of Nageezi, New Mexico, until the age of 23. Nestled in the state’s northwest corner, Nageezi is located just a short distance away from Chaco Canyon, a sacred and deeply personal place for many indigenous peoples throughout the Southwest. Growing up, Cly’s family immersed him in the Navajo culture. He learned the Navajo language and the tribe’s philosophies from his relatives and the schooling system.

Today, Cly is a doctoral student and a graduate research assistant in the UTSA Department of Physics and Astronomy. He began his studies at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, focusing on hologram physics, rocketry and robotics. Then, he moved to San Antonio, where he earned his master’s degree in physics at UTSA while working on the university’s Ph.D. program. He says UTSA has been the perfect place to reconnect with his Navajo roots and fully realize himself as a person and as a physicist.

In the following conversation, Cly shares more about the unique spiritual tie that Navajo communities have with eclipses. The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

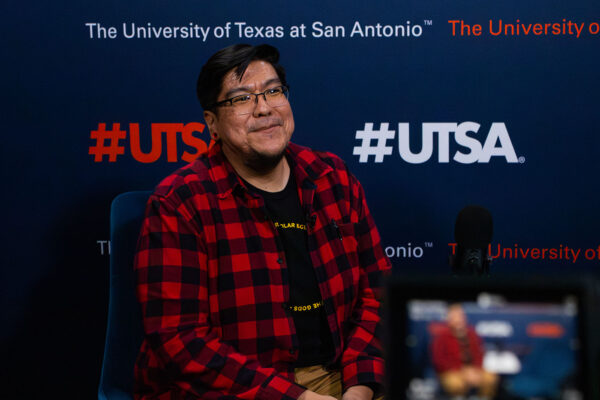

Cody Cly recently joined the Planet UTSA podcast to discusses eclipses and spirituality (and show off his Navajo eclipse t-shirt).

How does the Navajo tribe interpret the significance of solar eclipses?

Cly: We learn when we are young that eclipses are a time for renewal and reorder of the cosmos. It is time to pray for the sun. Teaching tells us to make an offering of corn pollen or cornmeal for the sun. We see the sun and moon as sacred beings akin to God — but not the gods. They represent male and female spirits, and this coming together signals a change and rebirth.

What do Navajo communities do to prepare for eclipses?

Cly: My culture views solar eclipses and lunar eclipses as a time to stop, pray and fast. During these events, Navajos do not go outside, sleep, drink water, eat, go to the bathroom or engage in intimate relationships. If these rules are broken, it is seen as knocking ourselves out of alignment spiritually, physically and mentally. With respect to fasting, we are told we will have problems such as digestive issues. If we look at an eclipse, we will have issues in the eyes. If you sleep during the eclipse, it is said you will suffer from sleeping ailments.

Are there any deities or spirits in Navajo mythology associated with the sun, moon or eclipses? What role do they play in a phenomenon like a total solar eclipse?

Cly: Yes. In my culture, the sun and the moon are holy beings. The sun represents a male being and the moon a female being. The sun is the being that keeps away monsters from the Earth. During an eclipse, when the sun goes behind the moon, it is believed these monsters return and roam the Earth in a spiritual sense.

How do Native American perspectives on solar eclipses contribute to an understanding of astronomy?

Cly: Every indigenous culture around the world has contributed to astronomy in its own way. We all have been here for thousands of years, and we had time to sit and observe. The ancient people of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon were probably the first people to record an eclipse before the European world. Indigenous people have always been observing.

Before colonialism, we used a lunar calendar. Certain stars were only visible at certain times of the year, and we used them to tell what time of year it was. The night sky informed us when to plant crops and harvest. There are certain ceremonies that are done at a certain time, and we use the night sky to guide us.

A lot of people talk about the North Star. Native Americans used it as well.

How do Native American teachings on eclipses inform their views on ecology and the environment?

Cly: We are told animals are paying respect to the sacred order in the universe. The birds stop singing, and the insects stop flying around.

How have modern times impacted Navajo communities, especially in terms of cultural revival or interest in traditional practices around eclipses?

Cly: Modern times have brought unique viewpoints. There is often a spectrum of these beliefs and mixing of traditional culture and modern-day culture. We are learning to adapt to these events. I do understand there are hard-working people who do not have the time to miss work or school and who may need to break these practices. I stand with the working class by doing work, but being an academic has given me some graces to keep a few key practices such as not eating, drinking fluids or going to the bathroom.

Yes, there is a revival of these practices. It is amazing, we were once punished for practicing our cultures. Colonialism has left a lasting scare on us, but this is an amazing time. We are coming close to the centennial of Native Americans being given U.S. citizenship and the right to vote.

We have gone from being hunted down as savages to being U.S. citizens and reviving our languages and traditional values. In San Antonio, I am actively seeing indigenous people of Texas reclaiming their culture after many years of the state trying to erase them and hunt them down. Many indigenous Texans had to claim being Spanish to stay alive and survive. I now can witness their revival.