West Side Sound

UTSA researchers look to preserve the iconic music genre

When people talk about the Westside, they think of the vibrantly colored murals they see when driving over the Guadalupe Street bridge. They think of the Our Lady of Guadalupe veladora that watches over the community or the smell of puffy tacos that infuse the air when driving past Ray’s Drive Inn.

What many don’t always think of is the music that was born in the casitas on the Westside more than 60 years ago.

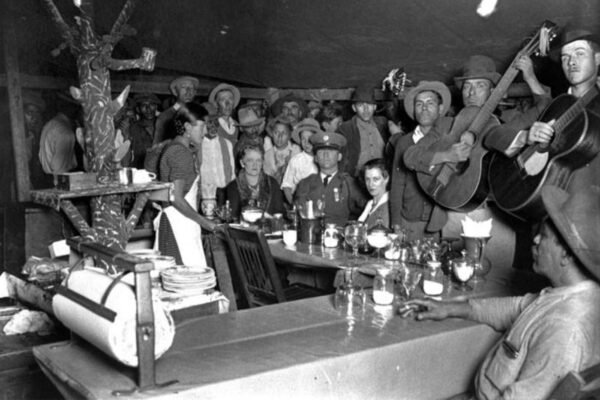

In the 1950s, local Westside teenagers strived to emulate the musical sounds that were sweeping through San Antonio via “the collision of sound” coming in from Louisiana, the East Coast and up north. The teenagers took the notes they heard from genres such as swamp pop, jazz, doo-wop, R&B, blues, country and rock n’ roll, added their spin and created what today we know as West Side Sound — sometimes referred to as Chicano soul.

“DJ and West Side Sound musician Henry ‘Pepsi’ Peña, who has the San Antonio Oldies Show, talks about how these trains from around the U.S. were carrying different music genres and collided on the Westside,” says Gloria Vasquez Gonzáles, a lecturer and co-director of the UTSA Mexican American Studies Teachers’ Academy. “When the trains collided, the notes went all over the place. The Westside teenagers picked up these notes and made the West Side Sound.”

“It’s done our way because of who we are. It can’t be duplicated exactly, so that’s what makes it unique. All of these influences are in there but done our way — Chicano style.”

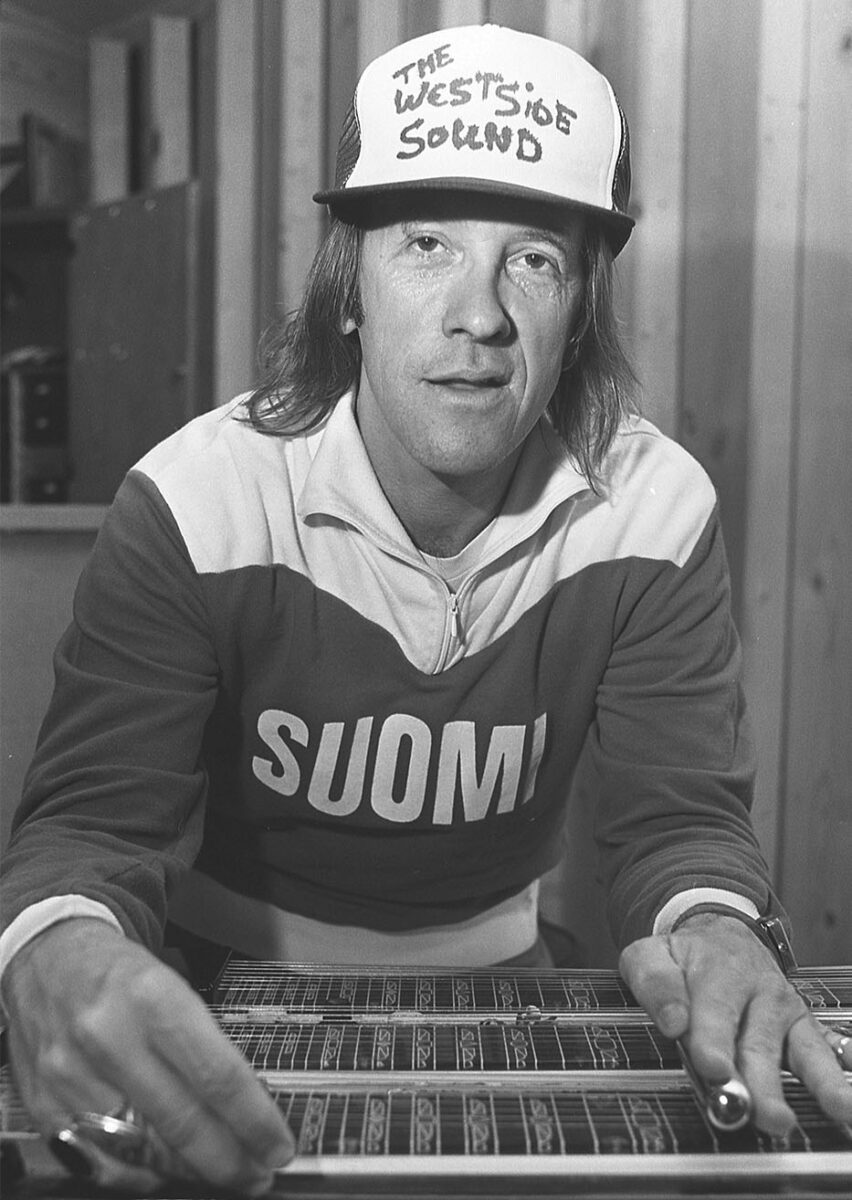

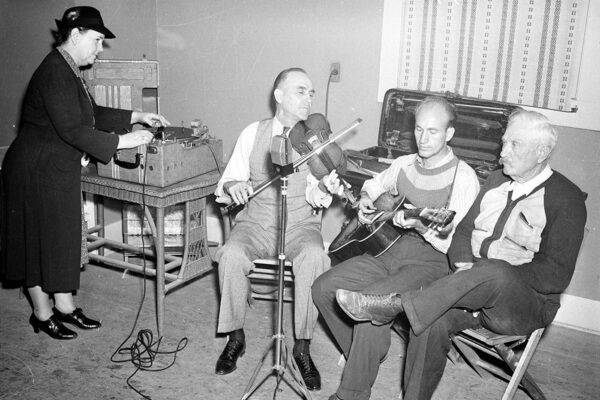

Today, Gonzáles, Sylvia Mendoza, an assistant professor in the UTSA Mexican American Studies program, and several community partners want to preserve the history of the West Side Sound through an oral history collection of photos and recordings.

With an urgency to document these musicians’ histories and a $5,000 grant from the UTSA Westside Community Center, Mendoza and Gonzáles launched the West Side Sound Oral History Project. Beginning in early 2022, it has since evolved from a simple list of names to dozens of community members eager to share their own West Side Sound memories.

“It has expanded in a sense that a lot of people want to tell their story. They want to talk about someone in their family or themselves,” Mendoza says. “I think folks want to see that representation in history. We have been contributing and creating, and I think it excites folks to see something coming out of a barrio in San Antonio.”

Finding their rhythm

West Side Sound developed during a difficult time for the Mexican American community. While the teenage years are supposed to be about having fun, many were instead dealing with the start of the Vietnam War, the Chicano Movement, San Antonio’s Edgewood High School walkouts and trying to find where they fit in society.

“They didn’t want to listen to the Spanish music their parents listened to because they have heard that all their lives,” Gonzáles says. “They wanted to play the music they were hearing on the radio and in clubs. These teenagers switched out the accordion of their parents’ music and instead used trumpets and organs to create a unique sound. They were rebelling and looking for an identity.”

“It was their way of saying, ‘this is who I am and who we are.’ I think they took pride in that. They were, of course, more aware of what was going on and were not putting up with it,” Mendoza says.

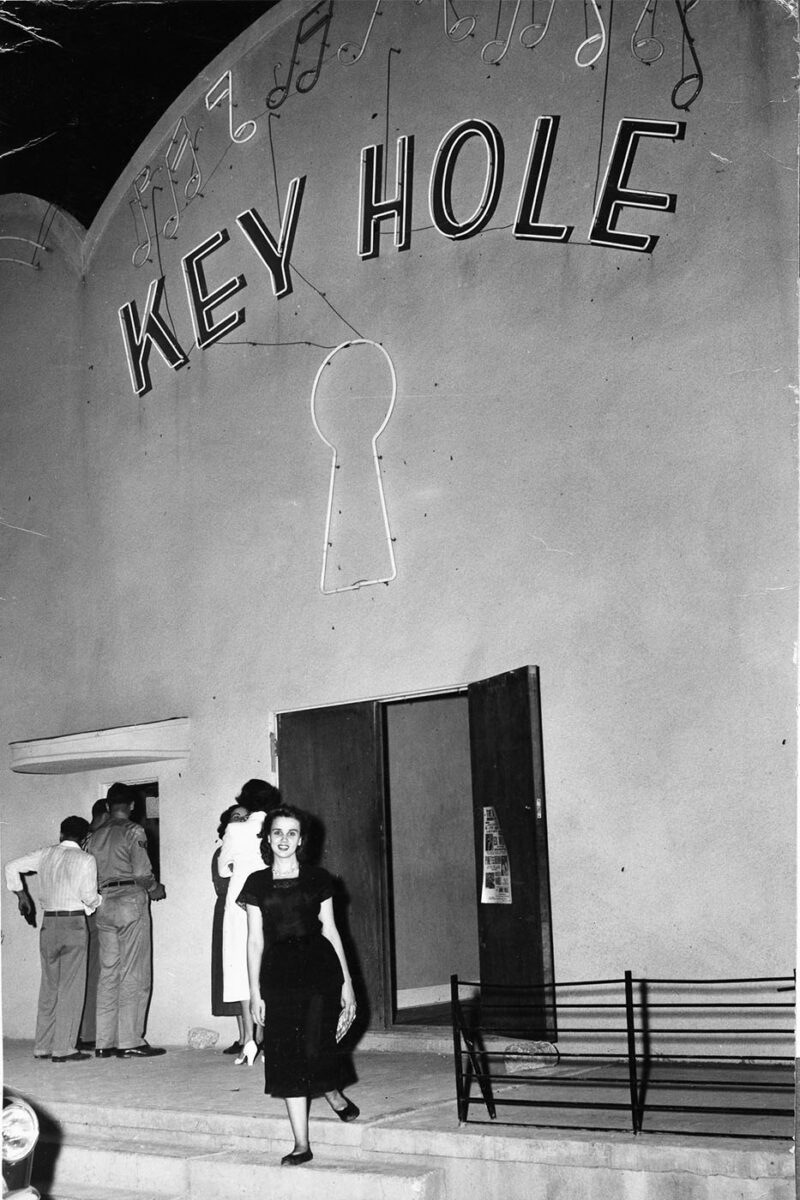

Aside from what they heard on the radio, the students also took notice of the music that was coming through San Antonio, including performances in what was then called the Chitlin Circuit. This was a group of venues that provided a space for Black artists to perform during racial segregation.

“San Antonio was one of the few cities that had integrated night clubs, some of them Black-owned,” Gonzáles says. “The teenagers would visit these clubs and listen to the music. They weren’t supposed to, but they did.”

One of the clubs was The Keyhole Club, which called itself the first integrated club in San Antonio, Mendoza says.

It’s believed that San Antonio’s status as Military City USA also played a large role in the musical influence, Mendoza adds. San Antonio’s military tradition meant that servicemembers, especially African Americans from places like Detroit, Chicago and New York, mingled with San Antonio’s Latino population.

From there, these teenagers took to their garages and developed their one-of-a-kind sound.

“They weren’t professional musicians but what we called garage bands. A lot of the students were in their high school’s band program and since their parents couldn’t afford some of the other instruments, the schools were able to get discounts or buy trumpets and saxophones,” Gonzáles says. “Those instruments are the unique characteristic of West Side Sound. Everyone we interviewed talked about the horns and the brass.”

While many of the teens were from the Westside high schools, the West Side Sound could also be heard in bands or groups that were formed in other areas of San Antonio such as on the Southside and the Eastside.

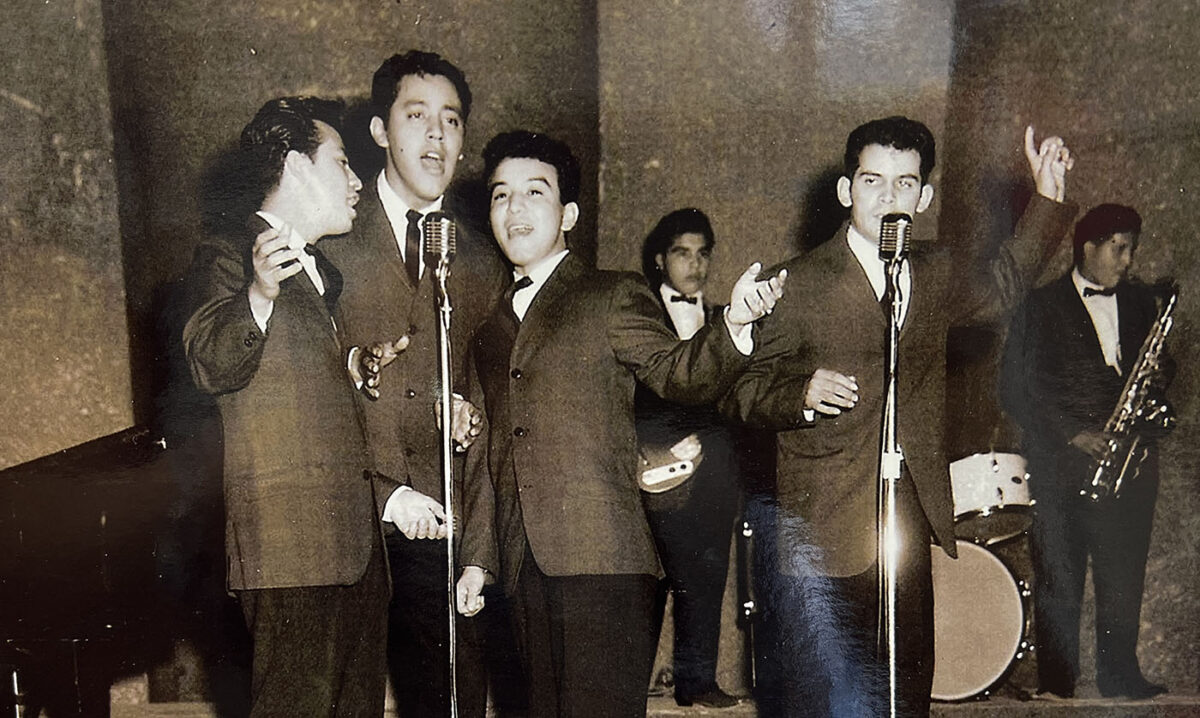

Many of the early pioneers of the West Side Sound include The Royal Jesters, Sunny & The Sunliners, Randy Garibay and Doug Sahm.

Remembering the venues

As Mendoza and Gonzalez recorded more and more interviews, the project became about more than preserving the music. It also meant preserving the memory of the venues where the West Side Sound could be heard, especially since many of the buildings no longer exist.

“When I interviewed my mom and tía, they talked about a lot of these sites that I never knew existed,” Mendoza says. “D&R on General McMullen was one of them. Patio Andaluz and Municipal Auditorium, which is now the Tobin Center, were some popular ones. My mom said that was one of the places where they would have the super bailes that took place all day long.”

Many of the sites that have been lost over time include recording studios where West Side Sound was recorded.

“Rambo Salinas, who is the general manager at Friends of Sound, has this idea for us to develop a site that shows you the recording studios that once existed in San Antonio,” Mendoza says. “They were houses and makeshift recording studios. We are preserving the oral histories, but creating a map of the actual studios that existed here is also important because the information can be lost over time.”

A new generation

While West Side Sound is still very popular among the individuals who grew up with it, the genre has now found itself in the ears of a new generation.

“On any given night you can go to Amor Eterno and somebody is spinning vinyl and it’s West Side Sound stuff,” Mendoza says. “You can go to Jaime’s Place and Squeezebox and they still have young people half my age listening to music that came out in the ’60s.”

Many of these younger individuals are becoming the knowledge keepers of this particular genre, Mendoza says.

“They have the collections and know how much these albums are selling for on the Discogs website,” Mendoza says. “I didn’t expect a lot of the younger people to be doing historical archival and research about West Side Sound.”

Gonzales adds that she believes the younger generation has taken to the West Side Sound because it’s a sense of pride for them as Mexican Americans.

“I think with this UTSA project and Mexican American Studies, it’s so important to know our history so we can feel empowered,” Gonzáles says. “It lets us know who created our music or who led the student walkouts. I think seeing that allows people to see that in themselves and know they can do that too. It makes them say, ‘I don’t have to assimilate and I can hold onto my identity.’ I think that’s why I feel the project is so important.”

A Musical Menudo

An inaugural book of the UTSA Press will showcase San Antonio’s rich cultural convergence of music

From the iconic accordion playing of Flaco Jimenez to Lydia Mendoza’s guitar talents and the local punk rock scene, San Antonio is a city at the intersection of many musical genres.

An upcoming book called The History of Music in San Antonio from the newly established University of Texas at San Antonio Press, is looking to share and preserve the history of San Antonio’s rich music scene. The project is a collaboration between the UTSA Libraries, the Institute of Texan Cultures and the UTSA School of Music.

Mark Brill, William Glenn and Stan Renard, all editors of The History of Music in San Antonio, describe the city’s music scene as a mixture — a menudo — of all its different elements.

“San Antonio’s ethnic groups are diverse, but they’ve mingled. They all have history on their own, but they have history together as well,” says Brill, associate professor of musicology and world music in the UTSA College of Liberal and Fine Arts. “We have the German, Czech, Polish, Mexican, Anglo and African American communities. We have so much here and it really is sometimes its own little stream, but at other times it’s a rich mixture of something that emerges and borrows from something else.”

The book will feature dozens of spotlights on the different musical elements of San Antonio from the music itself to the instruments created in the city, all told by more than 30 contributors such as musicians, educators and writers.

“It’s important for us San Antonians to formulate a sense of community, of identity. This is done by telling the story of who we are through music,” Brill says. “This is the land of conjunto. This is the land of Lydia Mendoza. This is the land of jazz and blues and Tejano. This is the land of Santiago Jimenez Jr. and Flaco Jimenez. That’s something humans have used throughout history to show who they are. This is a statement of identity for the city of San Antonio.”

The project, which is slated for release in 2023, has been years in the making, says Renard, associate dean of the Weitzenhoffer Family of College of Fine Arts at the University of Oklahoma.

“The genesis of this was when I was a professor at UTSA and part of a commission through the Department of Arts and Culture for the City of San Antonio,” Renard says. “One of our goals was to document the history of the music in San Antonio. We believed there needed to be a space where people could learn about the city’s music. And I said, ‘Hey, why don’t we do that at UTSA? We’ve got the archives and photos and interviews between the ITC and the UTSA Library.’”

Renard and Brill were going to write the book together, but they believed it could be so much more with other voices involved. So, they brought on William Glenn, head of reference and instruction for UTSA Libraries, along with the dozens of contributors.

The project does not end with the publication of the book. Brill said that there is a website that will continue to be updated with new discoveries, archival photos and recordings to give researchers and enthusiasts a go-to place to learn about the rich history of San Antonio’s music.

“That was one of the exciting things. We thought there is so much material and we can only put so much in the book and tell so many stories,” Glenn, head of reference and instruction and music librarian at UTSA Libraries, says. “We were initially going to approach University of Texas Press or Texas A&M University Press with the book idea, but we wanted to have control of the ongoing collection and publication of material. So, we approached Dean Hendrix at the UTSA Libraries about starting a UTSA Press so we could keep the project going the way we felt it should.”

A Collision of Hip-Hop and Academia

Marco Cervantes brings his passion for hip-hop music into the classroom

Lyrics about el mal de ojo, a superstition in the Mexican community, and the pachuco counterculture are just some of the references people can hear in the music written and rapped by artist Marco Cervantes, also known as Mexstep.

Cervantes is an associate professor in the UTSA Department of Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality Studies (REGSS) and the Mexican American Studies (MAS) program. For more than 15 years, he has used his passion for both music and scholarly work to talk about social justice and cultural identity. He does this as a solo artist but also as a member of a local San Antonio hip-hop trio, Third Root.

Sombrilla Magazine spoke with Cervantes about his love for the genre and how he uses it to teach his students and carry on his culture.

Let’s start from the beginning. How did you get started in music?

It started at a very young age. I was just a huge fan of hip-hop. By the time I got to middle school, probably 7th grade, I felt like I could start writing songs and performing them with other students in the school cafeteria. All through high school, I was in little groups recording and doing community shows. Once I got out of high school, I started doing shows in Houston where I’m from.

I was kind of in-and-out of college at the time and then I was in the military for a little while, but the whole time I was always writing and recording. Hip-hop has always been a big love for me. Something about the lyrics and the art form has always spoken to me. I felt I’ve always had a place to express myself through rapping.

Houston is a huge mecca for hip-hop music and culture. How do you think that influenced you?

I feel my history with Houston rap is important because when I was starting to record music, I got opportunities to record in the same studios as a lot of MCs and local hip-hop acts, such as The Geto Boys and UGK. Growing up in this hip-hop environment impacted the way I write lyrics and approach music. If you listen close enough, you can hear their influence in the lyrics I write.

How and why did you decide to integrate the worlds of hip-hop and academia?

I was working with UTSA faculty Ben Olguín, Norma Cantú, Joycelyn Moody, Sonia Saldívar-Hull and other really amazing mentors like Keta Miranda and Jose Méndez-Negrete who encouraged me. They would look at what I was writing in class and take note of what I was doing out in the community. I felt through conversations with them, I had the confidence to connect the two worlds.

Also, the reading I was doing on the Black arts movement, the Chicano movement and looking at how important poetry and music were to these movements — I felt what I was doing at the time was an extension of that.

Local hip-hop artist and UTSA professor Marco Cervantes, or Mexstep, performs at The Little Carver Civic Center on San Antonio’s Eastside. I Photos by Brandon Fletcher

What are some of the topics you explore in your music and lyrics?

Identity, of course and different injustices. I talk a lot about institutional racism and pointing out some of the issues but also using music in a way to help myself and others push on. I write a lot about pride itself and pride in culture. I think with this is something I really tried to do with my latest album Vivir, like with songs “Dale Shine,” for instance. I talk about the history of the Pachucos, and of the dressing up in the zoot suits and the low riders, and how those expressions create a sense of pride in yourself and who you are. Also, Black and brown love and solidarity is a big part of what I work on with my music.

How do you incorporate your music in the classrooms?

I teach classes about culture and history. I feel like music is a big part of the Mexican American and Chicano culture and history, for sure, when you’re talking about corridos, conjunto and Tejano. If we’re talking about the larger scope of Latinidad, there’s Cumbia and Bachata and other Black diasporic genres. All of these musical genres have histories connected to them. Music has been a way to talk about those histories.

UTSA professor Marco Cervantes, or Mexstep, performs with Andrea “Vocab” Sanderson at The Little Carver Civic Center on San Antonio’s Eastside.

How do you feel you are helping preserve the community’s culture and history?

That’s really important for me. Some of the musical choices, in terms of genre that I either sample or replay, I try to take from Chicano soul, Tejano, cumbia and trying to preserve that music because it’s such an important part of my identity. Even just making references to our community’s histories that we don’t hear about is another way of preserving our history. I don’t just freestyle — I want to give history lessons through the music.

MAS Corazón, Mas Cultura

A new ensemble at UTSA strives to break barriers for music and culture

When Rachel Cruz, assistant professor in the Department of Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality Studies (REGSS), first came to UTSA in 2020, her goal was to develop a degree plan with an emphasis in Mexican American music.

Since then, she’s done just that. Now Cruz is breaking barriers with a new ensemble that explores genres beyond Mexican American music.

The ensemble, which is called MAS Corazón, is an evolution of the San Antonio all-star phenomenon previously known as Mariachi Corazón de San Antonio, led by Cruz.

“Before coming to UTSA, I was working as an artistic director for Mariachi Corazón de San Antonio,” Cruz says. “Together with Provost Kimberly Espy and Dr. Margo DelliCarpini, the former dean of the College of Education and Human Development, we put our brains together and decided it would be a good idea to use Mariachi Corazón San Antonio as the catalyst for a pathway into Mexican American Studies (MAS). It has since evolved into an actual Bachelor of Arts degree with an emphasis in Mexican American music.

“Today with the internet and all, there is nothing off limits. I was asking my students, ‘What is Latin music? What is Latinx music? Who’s it for and are there age limits?’ It’s a rhetorical question because I think the answer is there are no limits. There are no limits to what defines Latinx music or Chicanx music.”

MAS Corazón, a new course and ensemble in the UTSA Mexican American Studies program, explores the music of the Mexican American culture.

The ensemble isn’t just stopping at the traditional guitarrón and vihuela.

“We’re incorporating all of the instruments from the different border music genres like mariachi, conjunto, orquesta, Tejano,” Cruz says. “There’s nothing off limits. If you can play the spoons, bring them. If it’s an instrument and it makes sound, orále, bring it. We’re playing songs ranging from ‘Chasing Cars’ by Snow Patrol in Spanish to ‘Havana’ and ‘Senorita’ by Camila Cabello, and many of my original compositions.”

Beyond the instruments and music, MAS Corazón will examine the historical development of Mexican American music, the cross-cultural interactions and influences and its role as an integral part of Mexican American society, culture, education and economy,” Cruz says.

While MAS Corazón is open to all UTSA students, Cruz hopes it can also serve as a pathway into the MAS music program for high school and community college students.

“If there are students who are in high school and are proficient performers and interested in getting a leg into the university, we will accept them into this ensemble,” she says. “I would love MAS Corazón to turn into something like a freshman interest group that they can stick with all four years to help facilitate their higher education success.”

For Cruz, who has shown South Texas students her love of mariachi music and how to connect to the Mexican culture through it for the past 24 years, this ensemble is about more than just winning competitions.

“I want to use MÁS Corazón as a catalyst for growth, as a catalyst to grow MAS and REGSS. I think through this ensemble we’re going to be visible,” she says. “It’s about validating this music as an art form that is valued and worthy of study. It’s a music that creates social change. It’s music with a message.”

2 Comments

Lovely read!

Ari, so glad you enjoyed reading the story!