In a village in the foothills of Ecuador’s Andes mountains, Cesario Lucitante, a shaman in the Cofán Nation, prepares for his healing ritual. He drinks the hallucinogenic ayahuasca, and the session begins. In a small wooden hut dimly lit, he chants and crunches in his mouth what sounds like gravel, and for hours he performs ancient healing rites to extract the illnesses that reside within his patient.

When we think of Indigenous shamans, it’s common for us to think of healing rituals such as this, but our ideas are often simplistic and one-dimensional. As Michael Cepek, professor of anthropology in the UTSA College of Liberal and Fine Arts, dives deeper into his understanding of the Cofán people, the expansive and complex knowledge of the shamans becomes increasingly fascinating. With support from a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, his experiences researching Cofán shamanic practices will be described in a book co-authored with Lucitante entitled, “Visionary Violence: Shamanism, Dispossession and Death in Amazonia.”

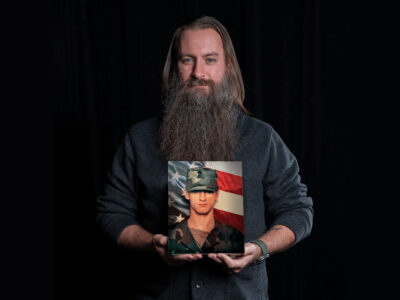

For more than 30 years, Cepek has committed himself to activism and research with the Cofán people, living among them and learning their ways. He decided early in his career that he would not be an anthropologist who conducts research solely as a consumer of knowledge. When he began working with the Cofán, he made a lifelong promise to them to work alongside them and do everything in his power to fortify their future against the pressures of displacement.

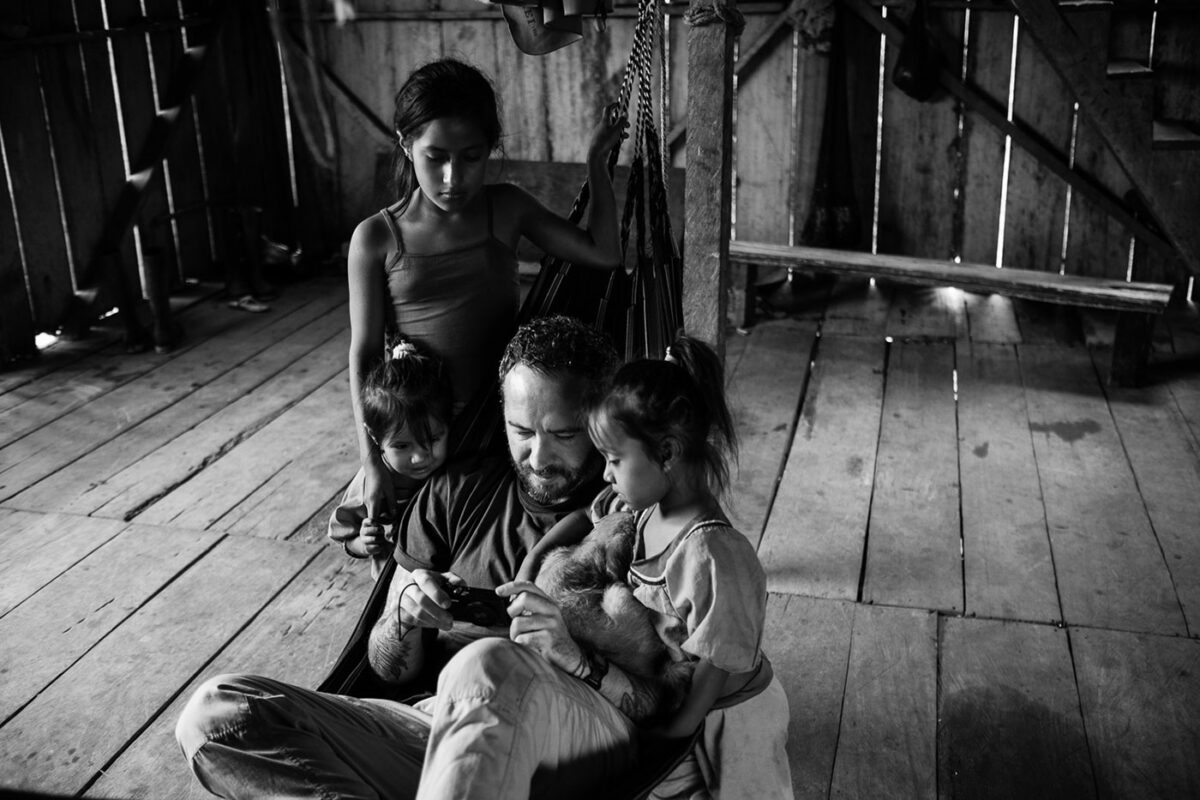

Photos courtesy of Bear Guerra

Cepek makes it clear that trust is at the root of everything he does among the Cofán. He shares that the first and most important step toward earning their trust was to learn their language. “The time and effort it takes to learn the language is a symbol of how much you care about people. And it allows you to talk to everybody, not just the people who’ve gone to school and learned Spanish,” he says. “The Cofán language is spoken in the house, and knowing it allows me to be part of the conversations, to joke and to know how to make people laugh.”

Cepek earned permission from the Cofán shamans to capture extensive video footage of their healing rituals. To gain a deeper understanding of what he captured, he sat with Lucitante and his son, Octavio, also a practicing shaman, for extensive hours collaboratively reviewing the videotapes.

Cepek recounted a time when they worked together to describe a moment in the footage. “How do you say the word for soul?” Cepek asked them. The three men went back and forth, trading insights rich with Indigenous ways of knowing, questions on the nuances of the Cofán language and insights that will be revealed in their forthcoming book.

“They know so much about their culture, but it’s embodied knowledge. A lot of shamanism is visionary knowledge. It’s not something you tell people; it’s something you know through direct experience,” he explains. “To get someone else from a different culture to understand it is hard, even if they consider you partially part of their culture and you speak their language. They’ve never had to do that before. It was really intimate.”

Photos courtesy of Michael Cepek

The Cofán people experience several threats to their territory, mostly from oil companies. Cepek’s 2018 book, “Life in Oil: Surviving Disaster in the Petroleum Fields of Amazonia,” assesses how 50 years of oil extraction has impacted Cofán lands, their lives and how they have managed to maintain a meaningful existence in this petroleum-saturated environment.

Throughout these decades of work, Cepek has advocated and supported the efforts to strengthen the Cofán people’s position in the face of these threats. He now serves as the president of the Cofán Survival Fund, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) that supports Cofán-directed environmental, medical and educational projects in Ecuador. Together they launched the Cofán Higher Education Project, which has now secured more than $300,000 to support the primary, secondary, undergraduate and graduate education of Cofán students in Ecuador’s best schools and universities.

“Some will go into law and become lawyers and some will go into medicine. And that can really save a people. It really can,” Cepek says.

Cepek has also recruited and secured funds for two English-speaking members of a Cofán community to earn their doctorates in anthropology at UTSA. He is advising both students as they study the culture, history and politics of their people to become the first Indigenous Amazonians with doctorates in anthropology from a U.S. institution.

Research and activism blend seamlessly for Cepek as he works for Cofán political causes, including policy papers, expert reports, amicus briefs and documentary films. His vision is to secure the expertise and leadership capacity within the Cofán community. He is committed to creating an archive in which every single piece of data, field note and video that he has collected will belong to the Cofán Nation.

What a wonderful article. It warms my heart to read of someone´s true dedication to indigenous people. I lived in Ecuador a mere three years to teach in a new private school, Colegio Menor San Francisco de Quito more than 20 years ago and after all these years and our travels, Ecuador and Africa are two of my favorite places. I feel connected to the people. Had a chance to tour the jungle. Has a natural beauty along with its people.

Thanks for reading the wonderful work our professors are doing out in the world! And thank you for sharing your connection to Ecuador.